Pop into any branch of discount supermarket chain Aldi and you will find something missing from its shelves. Cigarettes… and other tobacco products. Banning tobacco was a decision that caused a bitter rift between the German brothers who founded the supermarket.

But there are now hopes that the business split it caused will finally be mended, after more than 60 years. Those decades have been pockmarked by bitter family rows, accusations, squabbling over inheritance and even a kidnapping.

Now, the two sides of the family are in talks to bring the sundered halves of the firm together again. If they do make peace, they could create a grocery titan with more than 10,000 stores worldwide, eclipsing almost every competitor. By contrast, Tesco, the largest supermarket in Britain, has around 5,000.

Such a prospect would make Aldi an even more powerful force in the UK, where it is already the country’s fourth-largest grocer.

The chain is a favourite with British shoppers – not just cash-strapped families, but also middle-class customers in search of value. But many customers have no idea there is not one Aldi, but two. Still less are they aware that its founding dynasty has been plagued by family feuds.

The business was set up by brothers Theo and Karl Albrecht in the German city of Essen in 1946 when their country was rebuilding itself from rubble. Both had served in Adolf Hitler’s Wehrmacht in the Second World War. Theo fought in North Africa under the Desert Fox, Erwin Rommel. Karl was wounded on the Russian front.

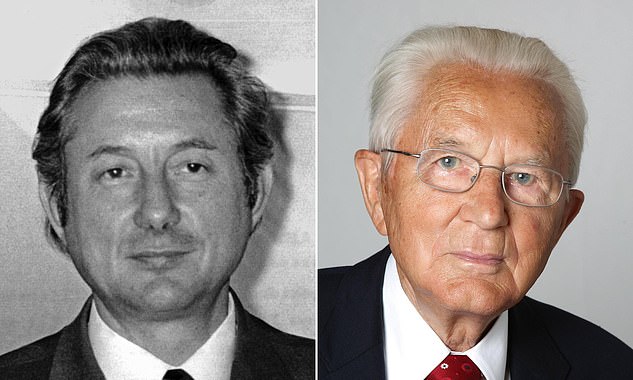

Warring brothers: Theo Albrecht, left, and his brother Karl founded the supermarket

The pair returned to ruins after a spell in a prisoner of war camp and took over their family’s small grocery store.

They quickly expanded, using fierce cost savings to keep prices low. This was needed if they were to attract hard-up customers in an economy under Allied occupation.

Aldi is a shortened version of the discount store’s original name, Albrecht-Diskont. The stores did not advertise, as that would cost money. In one of his rare public remarks, Karl said Aldi’s only advertising was ‘the cheap price’ of its wares.

The spartan decor became legendary: some early outlets didn’t even have shelves. This frugality extended to the brothers’ personal lives, too. Theo was known for using pencils until they were worn down to a nub. He wore loose-fitting suits so they would still fit if he gained weight, and ate cheap meals mainly of potatoes.

He is also said to have complained that the paper used for a blueprint for a new store was too thick and to have asked for a cheaper, thinner alternative. Both men were quick to switch off lights to save on electricity.

Aldi’s growth continued throughout the 1940s and 1950s, but matters turned sour in 1961 when the brothers argued over whether to sell cigarettes. Theo wanted to offer tobacco, but Karl believed it would attract shoplifters. The disagreement resulted in the business being split. Theo took charge of Aldi Nord (north), which did sell tobacco. Karl oversaw Aldi Sud (south), which did not.

They agreed not to compete against each other, so the business was partitioned in 1962 along a line which is known as the Aldi-Aquator, or Aldi Equator, and is still in place. Aldi Sud expanded from southern Germany into the UK and other countries, including Italy and Australia. Aldi Nord has stores in Spain, France and Poland, as well as northern Germany.

Both brothers were, by the early 1970s, incredibly rich. In 1971, their wealth led to Theo being kidnapped at gunpoint by a convicted burglar ‘Diamond’ Paul Kron and his crooked lawyer, Heinz Joachim Ollenburg, who had large gambling debts.

They kept Theo prisoner in a cupboard in Dusseldorf for 17 days, demanding a £1.5 million ransom. The cash, paid from the Albrecht family coffers, was dropped off at a rendezvous point but the kidnappers were arrested shortly afterwards. Only half of the money was retrieved. True to his miserly ways, Theo is said to have haggled doggedly with his abductors in an effort to lowball them on his ransom. And he later tried – unsuccessfully – to have the money written off by the taxman as a business expense.

The ordeal made the family withdraw even deeper into private life. Theo built a secure estate for himself and the rest of the Albrecht clan in a remote part of Germany’s Ruhr Valley. He began travelling to work in an armoured car, using a different route each day.

Sign of the times: Theo Albrecht, led Aldi Nord (left), while Karl ran Aldi Sud (right), which has since expanded into the UK

Karl also took drastic measures to ensure his privacy. In 1976, he built a golf hotel in southern Germany that included a private bungalow connected via a tunnel to the course so he could avoid being spotted when going to the links.

Theo and Karl continued to head their respective companies until the 1990s. Theo retired in 1993. Karl stepped down as the chief executive of Aldi Sud in 1994, but remained as chairman until 2002.

When Theo died in 2010, aged 88, he was Germany’s second-richest man with nearly £14 billion. His wealth was surpassed only by his brother, who died four years later at the age of 94, worth £15.5 billion.

Aldi opened its first British store in Birmingham in 1990. By the time Karl died in 2014, the firm controlled 4.6 per cent of the UK’s grocery market. Today, this has grown to 10.8 per cent, according to data firm Worldpanel.

Aldi made £537 million on sales of almost £18 billion in the UK and Ireland in 2023. Results for last year are due tomorrow.

Sidelined: Berthold’s widow Babette

Both parts of the Aldi empire remain in the hands of the Albrecht family, who control the respective businesses through a network of trusts. But drama has continued to haunt the clan. In 2012, a feud erupted following the death of Theo’s son, Berthold, whose will tried to limit the control of certain family members over Aldi Nord.

Matters escalated in 2018 with the death, at 92, of Cacilie Albrecht, Theo’s widow and Berthold’s mother, known as the ‘grand dame’ of Aldi. Cacilie’s will demanded that five of her grandchildren and Berthold’s widow Babette be kept out of business decisions. She accused them of lavish spending that was not in keeping with Aldi’s pennywise philosophy.

That dispute thrust the family into an unwanted spotlight. It was only settled in 2023 when a deal was struck to change the ownership of Aldi Nord so that all family members had an equal share.

Reports emerged from Germany in June this year that the thaw in familial relations could go further and that the split between the firms may finally be repaired.

The families are said to be in talks to merge into a single company, with control divided equally between them. The division over cigarettes has also eased, and some Aldi Sud branches now sell tobacco.

Given the family’s legacy, there remains the possibility of a fresh schism. But if they can put the past behind them and strike a deal, the prize will be great.

DIY INVESTING PLATFORMS

AJ Bell

AJ Bell

Easy investing and ready-made portfolios

Hargreaves Lansdown

Hargreaves Lansdown

Free fund dealing and investment ideas

interactive investor

interactive investor

Flat-fee investing from £4.99 per month

InvestEngine

InvestEngine

Account and trading fee-free ETF investing

Trading 212

Trading 212

Free share dealing and no account fee

Affiliate links: If you take out a product This is Money may earn a commission. These deals are chosen by our editorial team, as we think they are worth highlighting. This does not affect our editorial independence.

Compare the best investing account for you

#Bitter #family #feud #split #Britains #favourite #budget #grocer