Bryan Brown gives a barely perceptible nod of welcome after I arrive by ferry at Balmain wharf, as he steps out from under the semicircular roof of the late 19th-century timber shelter here, the last of its kind on Sydney harbour.

“How’s it going?” he asks, his Australian drawl at once familiar from his roles in 80-plus films and television series.

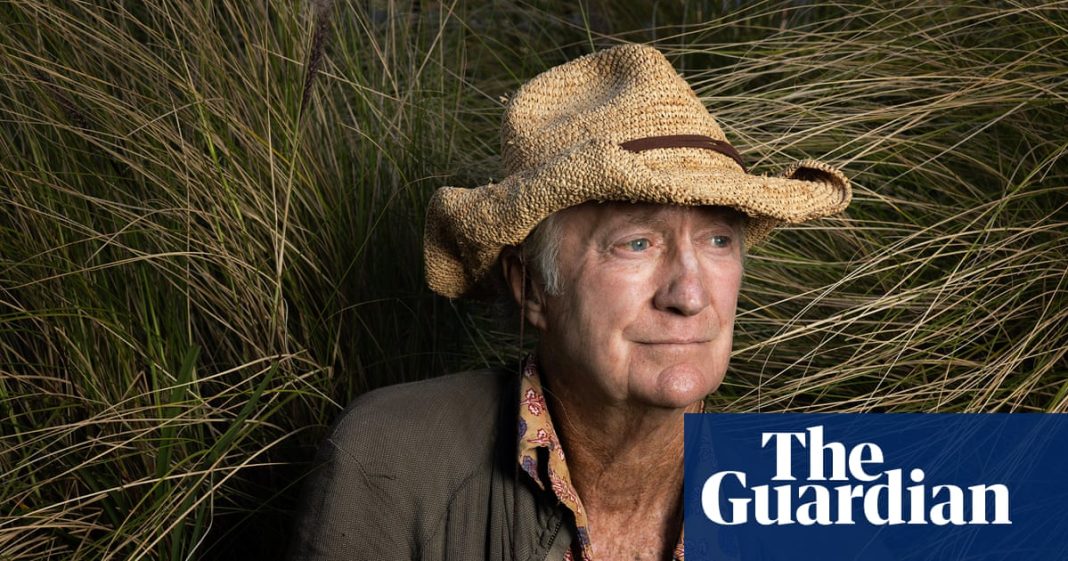

The actor wears a straw hat and sunglasses with a waist-length jacket partially zipped against a rugged late-afternoon north-westerly. He looks like a mysterious character from his recent career as a writer of crime novels populated by police, perverts and dope peddlers.

“I get the ferry from here [to Cockatoo Island] every now and again when I got nothin’ to do,” he says after we walk past hundreds of donated books lining the walls of the shelter, which doubles as a street library.

Brown is a “bit of a potterer”. He will have coffee in various shops along these streets before sitting at his desk between 11am and 1pm to write daily for “two hours, no more than that”. His second novel, The Hidden, just released, includes drug running in regional Australia by bikie gangs, hidden cameras and cockfighting.

He insists he doesn’t have a style – though he writes in workmanlike, staccato sentences, emphasising a Strine vernacular. “For the past 50 years, I’ve been telling stories and working in film and television. I work with writers, I do produce as well. So, maybe, that lends itself to how I see stories.” He’s ever curious about people, asking about how I got my start in journalism.

Given the windy day, we forgo our mooted plan to walk up along the water edge, instead heading inland up steep, narrow streets past a mix of weatherboards and double-storey Victorian brick terraces. Now a three-times grandfather, Brown is not as tall as you might anticipate given his charismatic screen presence, but at 78 he is lean and agile thanks to stretching, bending and weight resistance each morning, having taken up pilates 10 years ago.

There’s a busyness to Brown, his next acting gig always in plain sight. His latest feature, The Travellers, filmed in Western Australia, was released in cinemas in early October, reuniting him with director Bruce Beresford more than 40 years after they made Breaker Morant together. There are plans to make a third series of comedy-mystery Darby and Joan, in which Brown co-stars with Greta Scacchi, with his wife, Rachel Ward, continuing to direct some episodes. “I don’t like the idea of sitting in, stopping or anything,” he reflects. “I don’t even think about not working, you know?”

Ward, whom Brown met when they were cast together in the 1983 miniseries The Thorn Birds, spends much of her time in the Nambucca Valley, 500km north of here, having turned their one-time pig and cattle property investment into an exercise in regenerative farming.

Brown has no plans to go and live permanently in the Nambucca Valley himself, however. “I can’t,” he says. “Well, I mean, maybe one day, but I can’t 1764339684 because I film.”

Nambucca is clearly an inspiration for the New South Wales north coast setting for The Hidden. Besides guns being run, there is meth, coke and heroin in the community.

“It’s a work of fiction, of course, but you’d be a dope not to know that drugs are in society,” he says in his laid-back, straight-talking way, as we puffily continue our ascent via McDonald Street.

“There’s a lot of people struggling with housing, struggling with jobs, and struggles can sometimes lead to people going, ‘I need some relief’ and the next minute they’re into something, and that could be the downward spiral.”

Brown, born in 1947, grew up with his sister in Panania, a south-western Sydney suburb, raised by their mother, Molly, whom he sometimes accompanied when she cleaned people’s houses. “She never envied them or anything, she always was admiring that people had done things, but it never made her feel less, you know?”

His father, Jack, a salesman, left the family when Brown was a toddler, and the future actor only saw his father again a handful of times. As a child he spun the false story that his father had been killed in the war.

Perhaps he was a storyteller of sorts even if he could never imagine being a novelist back then, I suggest after we sit on a park bench.

“Yeah, maybe,” he smiles. “I didn’t want to say the truth, I guess. I don’t know if I was ashamed or went, ‘I’m not going to tell people that I’ve got a dad who’s never at home.’ So, the easiest thing was to say ‘ain’t around’, and [if they asked] ‘what happened?’ ‘Oh, he died in the war.’”

Brown then segues into how years later he had to set an old friend straight about this lie. As he talks about this time in his upbringing, he seems a little as though he’s writing a plot twist about a fictional character.

At age 20, Brown might have become a salesman himself had he not been invited to audition for an end-of-year review at the AMP insurance company where he’d been working and studying to become an actuary for three years.

“I joined an amateur theatre for four years, until I went, bugger this, I’m going off to England to become an actor,” he recalls, frustrated that Australian theatres mostly then favoured British and American plays over local stories anyway. “That comes down to Mum too. Like, ‘Bugger this – you wanna do it, do it properly, get on a plane, go over there, knock on doors.’ I think I found rejection quite easy because I’d been a salesman.”

In 1972, Brown went to Britain and “became a Pom” for two-and-a-half years, eventually winning some roles at London’s National Theatre in 1974, returning to Australia for a holiday in 1975 to discover a new wave of Australian voices: David Williamson in theatre, for example, and Fred Schepisi, Phillip Noyce and Bruce Beresford in film. Brown acted in productions for all of them. This new wave brought Brown back to these shores for good.

The eccentric character of Fred in Beresford’s new film The Travellers was written especially for Brown, but has elements of Beresford’s own father and story, concerning the tussle that ensues when an artist seeks creative fulfilment on international shores but is cut down as a tall poppy by some when returning to his home town.

Whether he is interpreting a character written for him or writing a novel, Brown believes everyone has a story, not least people from working-class communities like the one he grew up in. “Some of the stories just make you stand there with your mouth agape at the struggle that someone’s gone through,” he says. “And they don’t necessarily see that as a story, because they see a story as someone who becomes a fucking billionaire or a massive pop star. They don’t see their own life has a value and a respect, you know?”

A large, light brown curly furred canine drops its squeaky play ball at our feet. It has “assistance dog” written on its bib. Brown looks nonplussed at the expectant pooch, so I throw its ball, which it promptly catches and returns, hoping it will be thrown again.

Right now, as we head back down the street towards the wharf, Brown is marvelling at this new vocation of writing stories. A production company has picked up an option on his previous novel, The Drowning, but he won’t be writing the script.

“I’m not having anything to do with it,” he insists about any screen adaptation. “I’ve been a producer, where I buy the rights to scripts, and then the writer wants to start putting their two cents in there and be a pain in the arse.”

Brown is content right now to bask in being interviewed for audiences about his novels and screen roles on his book tour, happy enough for scriptwriters to run with his own words.

“I’m not gonna be the pain in the arse to someone else.”