When Nvidia posted blockbuster results 11 days ago the relief was palpable. The artificial intelligence (AI) pioneer – and world’s most valuable company – had eased growing fears that the tech bubble was about to burst.

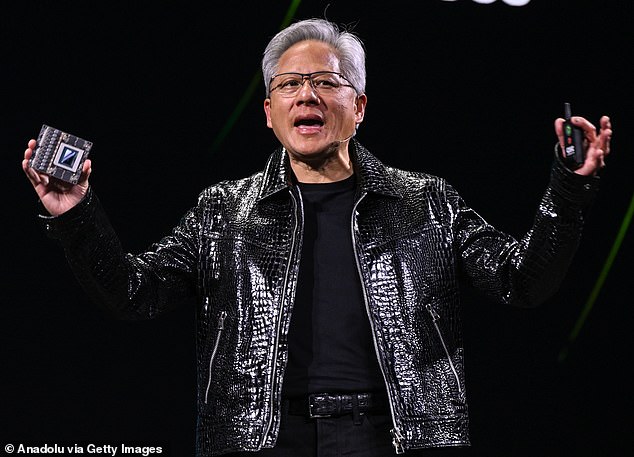

Demand for Nvidia’s state-of-the-art Blackwell computer chips was ‘off the charts’, said its leather-jacketed boss Jensen Huang.

‘AI is going everywhere, doing everything, all at once,’ he added.

The headline numbers certainly looked impressive. Turnover of $57 billion in the three months to the end of October was 62 per cent higher than a year ago.

Gross margins – a measure of how much of those sales are converted to profit – remained incredibly high at more than 73 per cent.

And net profit of $31 billion was two-thirds up on last year’s mark.

Crash: Nvidia boss Jensen Huang saw his firm’s value fall $700 billion in a month

But despite smashing analysts’ expectations, the euphoria didn’t last. Within hours Nvidia’s shares were on the slide as the backlash against the AI boom resumed.

From a peak of more than $5 trillion in late October, Nvidia has lost $700 billion in value.

‘The market did not appreciate our incredible quarter,’ Huang later told staff. Expectations were now so sky-high that Nvidia was in a no-win situation, he added.

‘If we delivered a bad quarter, it is evidence there’s an AI bubble. If we delivered a great quarter, we are fuelling the AI bubble,’ Huang complained. ‘If we’re off by just a hair, the whole world would have fallen apart.’

Instead, it is Nvidia’s world that is increasingly under threat.

Now it faces growing competition for its high-end processors from the likes of China’s DeepSeek and Alphabet-owned Google. The search engine giant has just released Gemini 3, its latest large language model, which is powered by bespoke chips rather than trained using Nvidia’s ubiquitous semiconductors that power ChatGPT, OpenAI’s rival chatbot.

Other tech giants such as Microsoft and Amazon are also developing their own custom-made AI chips to reduce reliance on

Nvidia’s expensive graphics processing units (GPUs) that have up to now cornered the market.

And the sheer amount of debt-funded capital pouring into AI has fuelled concerns that the revolutionary technology has become little more than a vast money pit where any hope of a return on such a huge investment vanishes.

OpenAI, for example, is at the centre of a complex web of ‘circular’ deals with Nvidia, Microsoft and software giant Oracle worth $1.4 trillion. Yet its turnover is a thousandth of that – $13 billion.

But for some it is Nvidia’s own knockout numbers that look too good to be true.

Foremost among the sceptics is Michael Burry – the ‘Big Short’ investor who famously anticipated the US housing crash ahead of the 2008 financial crisis and whose hedge fund recently made a hefty bet on Nvidia’s share price falling. In a post on social media website X, he claimed Nvidia was one of a number of AI companies that have ‘suspicious revenue recognition’.

More specifically, it is the practice of booking revenue after its products have been supplied but before invoices have been paid by customers. This tends to boost short-term earnings for a firm but risks bad debts piling up later if bills are not settled in full.

The true scale of the ruse – which is allowed under US accounting standards as long as the income has been earned – is buried in Nvidia’s latest results.

Its ‘accounts receivable’ – the amount of money owed for chips sold on credit but not yet paid for – soared by more than $10 billion to $33 billion in the third quarter.

In other words more than half of Nvidia’s sales have yet to be paid.

‘It does beg the question – if things are flying off the shelves, why aren’t you getting paid for it?’ asked Kimberly Forrest, founder of investment firm Bokeh Capital.

So who are these customers – and why don’t they pay on time? Nvidia won’t say who they are, but just six of them account for about 85 per cent of its total sales.

Two of them – referred to as Customer A and Customer B – speak for 23 and 16 per cent of revenues.

One view is that such customer concentration shows just how much Nvidia has captured the AI infrastructure market.

Its chips are essential for the physical data centres that store and retrieve vast quantities of text and video from the internet and other sources to train chatbots and other large language models.

And Nvidia’s main customers are thought to be data centre operators such as Microsoft and Amazon who are among the most stable in the world and whose spending on AI shows no sign of slowing.

But the risk of relying on just a few customers for the bulk of income is clear, especially if those customers decide to do their own thing and develop their own chips – or simply spend less on AI.

For Burry, this is just another reason to avoid Nvidia.

‘Almost all customers are funded by their dealers and propped up by a string of circular contracts rather than genuine demand from firms using the revolutionary technology,’ he said on social media.

True demand for AI tools was ‘ridiculously small’, he said, also claiming the way Nvidia accounted for its flagship GPUs was incorrect, as they had a shorter shelf life than the firm suggested.

In an extraordinary rebuttal, Nvidia hit back at Burry, saying in effect it was not Enron – the US energy giant that collapsed after an accounting scandal in 2001.

‘Nvidia does not resemble historical accounting frauds because Nvidia’s underlying business is economically sound, our reporting is complete and transparent, and we care about our reputation for integrity,’ it wrote to analysts.

‘Unlike Enron, Nvidia does not use special purpose entities to hide debt and inflate revenue.’

As its share price tumbled this month Nvidia went further, claiming its technology is ‘a generation ahead of the industry’.

‘It’s the only platform that runs every AI model and does it everywhere computing is done,’ it said.

But Burry stands by his analysis.

The stand-off matters because if Nvidia is right we are still in the foothills of the AI revolution, and the tech boom has further to run.

But if Burry and the sceptics prevail, a stock market crash will surely follow on a scale that will make the dotcom crash look benign. That’s because far more wealth is tied up in technology stocks today than back in 2000.

The so-called Magnificent Seven – Nvidia, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Facebook-owner Meta, Alphabet and Tesla – make up more than a third of the benchmark S&P 500’s total value.

And the US stock market itself accounts for about 70 per cent of the global MSCI index.

Some economists say without the AI spending boom, the US – the world’s biggest economy – may be in recession already. So if the bubble does burst, it won’t just be stock markets that catch a cold.

DIY INVESTING PLATFORMS

AJ Bell

AJ Bell

Easy investing and ready-made portfolios

Hargreaves Lansdown

Hargreaves Lansdown

Free fund dealing and investment ideas

interactive investor

interactive investor

Flat-fee investing from £4.99 per month

Freetrade

Freetrade

Investing Isa now free on basic plan

Trading 212

Trading 212

Free share dealing and no account fee

Affiliate links: If you take out a product This is Money may earn a commission. These deals are chosen by our editorial team, as we think they are worth highlighting. This does not affect our editorial independence.

Compare the best investing account for you

#Nvidia #turning #TRILLION #ticking #timebomb