Just a week on from Rachel Reeves’s chaotic and poorly received “more of the same” Budget, are you ready for the new paradigm? That is what Green Party leader Zack Polanski is calling his revolutionary way of thinking about the economy that turns almost everything we have long held true about how to run the country’s finances on its head.

We have already heard a lot about the wealth tax that would slap a one per cent levy on all assets worth more than £10 million and two per cent on those valued at £1 billion or more.

Less known but far more significant for most of us is the Modern Monetary Theory, or MMT, as it is known, that is the intellectual core of Polanski’s vision of a radically different Britain.

In essence Polanski believes that it is time for politicians to throw off the shackles of deficits, fiscal rules, OBR projections and gilt yields that they have been obsessed with.

He maintains that by adopting MMT the UK’s government can stop being scared of the City — the bond markets in particular — and become freed up to start spend heavily on infrastructure, the green transition and investment in health, education and welfare for the most vulnerable in society. It is what some call “the politics of care”.

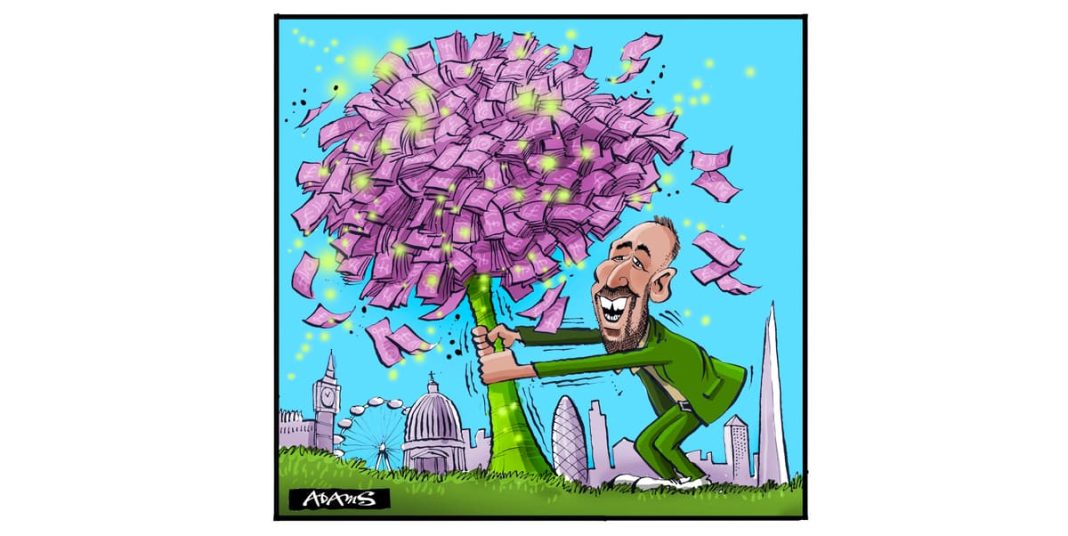

Zack Polanski’s Magic Money Tree

Christian Adams

While none are practicing professional economists, the trio have had a huge impact on the emerging thinking of Polanski and the party he leads.

What is MMT and how would it work in practice?

Polanski maintains that political leaders as far back as Margaret Thatcher have been feeding the country a lie. Contrary to their folksy analogies, the British economy is not at all like a family household that has to “balance its books” and face terrible punishment from the bond markets if it gets too heavily in debt. So the Green argument goes, government is the only organisation that can create its own money and should use that superpower for the benefit of all its citizens, particularly the most needy.

The family budget analogy is one that Reeves herself has frequently deployed, telling the BBC’s Nick Robinson in an interview earlier this year how she remembered “very vividly” her mother “sitting at the kitchen table with the receipts and bank statements and ticking them off to make sure she wasn’t overspending”.

MMT true believers — and the Green Party — insist everything about that comparison is nonsense. Worse, it has left successive British governments — not least the current one — cowering at the mercy of the bond markets, resulting in austerity-style public spending cutbacks that inflict untold harm on the most vulnerable in society. In Polanski’s words: “I don’t think the markets should be dictating democratic decisions.” Many would agree.

He believes Green-led government spending could avoid a Liz Truss-style meltdown because, as he told the BBC’s Laura Kuenssberg, “I’m talking about borrowing for capital infrastructure and investment to create spending multipliers that come back into the economy.”

So in a parallel universe in which MMT would be the dominant economic dogma, how would things be different?

In purely organisational terms there would be no need for an Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) for starters. There would simply be no role for the Whitehall body that marks the Chancellor’s homework and gets into heated debate with the Treasury number-crunchers about the odd billion here or there of government spending or borrowing.

Perhaps the fundamental core belief of the cult of MMT is that a government of a country with its own currency and its own central bank can create money to fund spending and fire up spare capacity in the economy. It is not and should not be constrained by artificial borrowing limits.

Under MMT, the only limit on government spending is the resources available in the real economy

Instead, the only limit on government spending is the resources available in the real economy, and the main tool to manage the economy is inflation, which can, in turn, be contained through taxes, like the boron “control rods” in a nuclear reactor.

Once that premise is accepted, the government is free to spend big without constantly having to look over its shoulder to check if it is about to be mugged by the bond vigilantes. Unemployment would be a thing of the past.

If MMT almost sounds too good to be true, there are many who say it is precisely that. For every paid-up member of the MMT fan club there are many detractors who see the theory as, at best, snake oil, and at worst a dangerous delusion that could bankrupt the country. For its critics MMT also stands for Magic Money Tree.

As one commentator colourfully put it, the MMT-ites are the economic equivalent of “flat earthers” or “toddlers who claim to see unicorns and then say we can’t prove they don’t exist”.

But perhaps the most famous put-down of MMT came from former Bank of England chief economist Andy Haldane, who summed it up: “It’s not modern. It’s not monetary and it’s not really theory.”

MMT is quite a Venezuela-style approach to running your economy

Simon French, chief economist and head of research at Panmure Liberum

For Simon French, chief economist and head of research at City investment bank Panmure Liberum and another sceptic, there may be an “in extremis” role for a temporary version of MMT during emergencies such as the financial crisis or the pandemic. But adopting it as permanent economic policy will only end in tears in the form of rampant inflation or a run on the currency. As he puts it, MMT is “quite a Zimbabwe-style or a Venezuela-style approach to running your economy.”

MMT is far from a new invention. It traces it roots to the Keynesian revolution in economic thinking of the 1930s. Joe Nellis, economic adviser to accountants MHA, describes MMT as a “first cousin of Keynesian economics — but more radical. It’s effectively proposing a jobs guarantee. Keynes wasn’t proposing that.”

MMT really hit the mainstream with the publication of Stephanie Kelton’s New York Times bestseller, The Deficit Myth, in 2020.

For all its radical implications and superficial appeal, MMT remains a frustratingly hard concept to explain in pithy one liners. But according to Murphy, one of the trio of thinkers mentioned by Polanski, who is Emeritus Professor of Accounting Practice at Sheffield University Management School, there is simplicity at the heart of it. He says: “If I sat down for two days with a really good advertising agency, I could come up with a great campaign to sell MMT to the public.”

Why does the City hate MMT? Because it wants to feel in charge

Richard Murphy

And he is dismissive of those in the City who view MMT with deep suspicion. As he puts it: “Why does the City hate it? Because it wants to feel in charge, it wants to feel they have got the power. But the key point about MMT is that the Government is not dependent on the City, it is the other way round. The banking industry, the pension system, life insurance and international trade… they are all utterly dependent on government bonds”.

For now at least, MMT remains a minority sport still well outside the economic mainstream, but it is gaining traction after what feels like decades of slow growth and stagnant living standards. And with the Greens polling at around 15 per cent, and within touching distance of Labour, its leading proponents could easily find themselves sitting round a coalition Cabinet table in less than four years time.

For a tired, jaded and in many cases impoverished electorate, MMT appears to offer a route out of the era of endless pessimism delivered by the mainstream parties.

But as Panmure’s French argues, even MMT cannot defy the economic laws of gravity forever. One day, sure as night and day, all those trillions of pounds of debts do have to be paid back.